The RCAF airmen and the Leksand Ice Hockey Club

– a fascinating unknown true story from Sweden during World War II

By: Lars Ingels

The Swedish sports club Leksand’s IF was formed in 1919 and included ice hockey as early as 1937/38. But matches against interned Canadian airmen during the 1943/44 season would play an important role in the development of ice hockey in Leksand and Sweden. These matches have been largely forgotten until now.

The first ice hockey game in Sweden was played in 1921 in the capital of Stockholm with long-reigning King Gustaf V among the spectators. But everyone was not convinced that ice hockey was something for Sweden. One journalist thought it looked like a circus show. The main skating sport on ice in Sweden then was “bandy”, which is almost like “field hockey on ice” played with short sticks and a ball.

The roaring twenties saw some increase in hockey popularity in Sweden but only in Stockholm and its surroundings. In 1927, Victoria HC from Montreal was invited to play five games in Sweden. At the time, about 80,000 Swedes lived in Canada. Today some 300,000 Canadians have Swedish roots.

In the 1930s Swedish teams occasionally played Canadian teams but hockey was still a sport mostly for Stockholm and the nearby districts. The last game against Canada before the war was played in 1938.

Hockey arrived in Dalarna county, in central Sweden, in the mid-1930s, introduced by a Swedish boat-racing world record holder by the name of Gunnar Faleij. He managed to overcome the lack of enthusiasm he met from the traditional bandy players in the small town of Mora, located on the north shores of Lake Siljan.

Leksand, on the other hand, was a small town just south of Lake Siljan. Leksand’s IF (IF is an abbreviation for Idrottsförening, which translates literally as sports association or sports club) had played bandy for two decades; however, it was tough financially and the players had difficulties in getting the big ice surface ready. It was the size of a soccer field and so in 1937 they quit playing bandy and decided to play hockey instead. A smaller ice surface seemed much better, although it was a sport they had never played, or even seen.

From one winter to the next the bandy players of Leksand became ice hockey players and the first historic match against arch-rival Mora IK (formed in 1935) took place in January 1938. Leksand won by 11–0. After three periods, the result was 8–0, but Leksand gave Mora an extra period to score. In vain. No wonder, this win is talked about happily even today among the many Leksand fans.

But the following years not very much happened on the ice hockey rinks in Leksand. World War II with its conscriptions interfered. Admittedly, local village team series were started for both seniors and juniors, but during the first six seasons, the Leksand’s IF team played an average of only three matches per season. It was different in Mora, some 60 kilometres up north, because Mora had an advantage: The great cross country ski race Vasaloppet (today the biggest in the world) drew huge crowds every winter and each year some Stockholm ice hockey clubs took the opportunity to come and play friendly matches, against each other or against Mora IK.

In the autumn of 1943, the situation was as follows: No team in Dalarna had yet played in a hockey league, despite trying to get a county series for a few years. Mora IK’s Gunnar Faleij, still an avid ice hockey enthusiast, had had a new ice hockey rink built, with stands and new electric lighting. He now wanted his team to play in Division II North, which in fact was a league mostly for the neighbouring county Gästrikland with its principal town Gävle.

But the Gävle teams were not particularly interested in doing the relatively long away trips up to Mora. So nothing came of it. But in Falun, the principal town in Dalarna, the local club Falu BS also had a strong man: Harald Andersson (former world record holder in discus throw) who just took over as chairman of the Dalarna Sports Association’s ice hockey section after Gunnar Faleij. As well as in Mora, this winter a completely new ice hockey rink would be built in Falun, right in the middle of the city, next to an educational institution.

In Leksand, on the other hand, they probably did not really know what to do; it had been a problem to get flushing hoses for the ice hockey rink ... But they still signed up for the first Dalarna series in ice hockey, which would consist of Mora, Falun and Leksand.

The war intervenes

It was now that the World War II dramatic events of over Nazi Germany intervened and would write a new unexpected chapter in Dalarna’s ice hockey history.

Canada had joined Great Britain in the war effort already in 1939. Sweden decided to stay neutral, hoping not to get involved. The country had not been at war since 1814. But the war would, of course, affect Sweden in many ways. More than 300,000 Swedes served in the Swedish armed forces, on high alert for the duration of the war. And both the German and Allied armed forces would use Sweden for transportation of troops to and from occupied neighbouring countries during various times of the war, with the silent consent of the Swedish government…

Adolf Hitler’s grip on Europe and North Africa had culminated in 1942, and especially in 1943 the Allies had intensified their bombing raids on Nazi Germany with their new four-engine bombers. The aim was to weaken the enemy before the coming invasion. Both British and American air bases were built at a furious pace in England to house all the planes that would fly to German cities and factories and drop their devastating bomb loads.

At night, the British Royal Air Force Bomber Command flew. But it also included pilots and airmen from other countries from the Commonwealth, such as Canadians, Australians and New Zealanders. During the day, however, it was American bombers from the United States Army Air Force that flew. They were better equipped to face enemy fighter planes and therefore flew in daylight. The British had a crew of seven men in their planes while the American planes had ten on board: pilot, flight engineer, navigator, wireless operator, bomb-aimer and machine gunners.

There were an enormous number of bombers that took off from England and flew towards the continent, sometimes up to a thousand planes per raid. This meant up to 10,000 airmen could be in the air at the same time! The losses were extremely high. Of the 125,000 bomber pilots and crew members who flew in the RAF Bomber Command during the war, 46 percent died. Although the aircraft developed during the war, the enemy also became more effective: the German air defence was expanded and the fighter aircraft received new technical aids.

The planes that were hit by fighters or flak but did not crash immediately obviously tried to get back home to England, but often such a long flight with a damaged plane was wishful thinking. In many cases, it was closer trying to reach neutral Sweden. Which more than 200 Allied aircraft did during World War II. This meant that about 1,500 Allied airmen came to Sweden. Most were Americans and most of them came during the intense bombings of 1944.

According to the Hague Convention, the airmen were to be detained in the neutral country until the end of the war or until they could be exchanged. So during the war, Count Folke Bernadotte was appointed head of the Swedish Section for Internment. He was a diplomat and also the nephew of the Swedish King Gustaf V. Count Bernadotte was given the responsibility of arranging for the airmen to be interned. These were thus not prisoners of war but would only remain in the country. Several locations were to be used, but one of the larger ones was Falun. The town was fairly far from the war scenes and already held an infantry regiment whose soldiers were to defend the Swedish borders. In 1940 a camp was hastily built in Falun to accommodate foreign military soldiers that came to Sweden, and who had to be interned.

In 1943 the bombers came to Sweden at an ever faster pace. And then in August 1943, during the intense bombings of Hamburg and Berlin, respectively, there were three damaged British Halifax bombers reaching southern Sweden after great drama to make an emergency landing or for the crew to be able to parachute out. These three RAF planes had partly Canadian RCAF crew on board. Not everyone had practiced parachuting, but as one of them said later when he was in Falun:

”When you are down on the ground thinking about parachuting, you think it sounds scary. When you are on a plane that is plunging down and the parachute is your only hope, you don’t hesitate for a second.”

The crew of the first Halifax bomber, HR871, managed to fly to neutral Sweden during the last night of The Battle of Hamburg, 2 August 1943, after being hit by lightning. They bailed out over the southernmost province of Sweden, Skåne, and then let the aircraft crash down into the Baltic Sea. The next Halifax had also a very dramatic last mission on the first night of The Battle of Berlin on 23 August, parachuting before the plane crashed on Swedish soil. The very same night another Halifax made a splash off the southern coast of Sweden.

All these airmen were transported to Falun. But the standard of living in the internee camp wasn’t what the Allied airmen were used to, to say the least. So in October 1943 it was decided they were allowed to stay at small hotels and guest houses in the surroundings of Falun. Soon these interned airmen in “the sleepy town of Falun” were bored from lack of action. They were safe but they didn’t know how long they would be kept in Sweden.

National interest in the first matches

Winter came to Falun in November 1943 and soon the rumour spread; here were some Canadians who wanted to play ice hockey! Contact was made and it soon became clear that they would be allowed to play with Falu BS. Of course, they were fliers in the first place, but Canadians as they were, they had hockey in their blood and several of them had played ice hockey at home in Canada.

The Canadian hockey players in Falun in 1943/44 came from five different British aircraft, first the three Halifaxes in August and then two Royal Air Force Lancasters dramatically crashed in southern Sweden in December 1943 and in January 1944. It meant that the Canadians could form their own team (there were nine men in a hockey team at that time). But during the winter, some of them were also sent back to England, so they replaced each other in the team so to speak. In the first place, the RAF needed to get back the pilots and navigators needed to fill the gaps that arose as more and more planes were shot down.

Almost no international sports teams at all came to Sweden by this time of the war, thus it was an unususal event with Canadian ice hockey players in Dalarna. The Stockholm press sent its reporters to the premiere match on 30 December at the new ice rink in Falun, between a Canada-reinforced Falu BS and Mora IK. The Mora players had already played four training matches together, while the home team only had had time for a few training sessions. In front of more than 1,000 spectators (a new record for ice hockey in Falun) Mora won 7–0. Falun had six Canadians in the team – the goalie, two defencemen, and three forwards – and in addition a Swedish line with three forwards. The rematch in Mora on New Year’s Day 1944 attracted almost as large an audience and now Mora won 8–1. The results diminished the interest of the capital’s press… Weren’t they better?

But the Canadians themselves were not so surprised. Most of them had not played after they were recruited on the air force… Now they wanted to get in shape. And they did. Starting with a local derby, the Swedish players of Falun played against “Canada”, resulting in a draw of 3–3. The Canadians in Falun would play a total of 20 ice hockey matches this winter.

“It was a great way to fight a war,” Canadian sergeant Jim Flick of the Royal Canadian Air Force later described the winter of 1944.

Due to the war and censorship of the Swedish press, the airmen were rarely mentioned by name in the Dalarna press’ reporting from the matches, so exactly how many players played this winter’s matches is unknown. But by all accounts, there were a dozen Canadians playing. In five of the matches, they appeared as “Canada”, otherwise they were part of the Falu BS team.

Leksand played the Canadians eight times

Mora IK did not play any further training matches against the Canadians. In addition to the league that would soon start, Mora devoted to arranging training matches against teams from Gävle and Gästrikland. Now it was important to prove that the Mora team was good enough to play in Division II next year.

This opened the way for Leksand, and for eight weeks they played on average one match a week against the Canadian Falu BS. Leksand won the first two matches; for the first home game, 600 spectators came to the outdoor rink Siljansvallen. A new record! The Leksand players then went to Falun, 50 kilometres from Leksand, in a big taxi driven by producer gas.

But when the league started, it was Falun who drew the longest straw in both matches. The schedule of Division III Dalarna included home and away matches between the three teams, a total of only six matches. But it was still the very first ice hockey series in the county. Mora won the series by seven points, ahead of Falu BS’ Canada-reinforced team with four points and Leksand came last with one point after finishing 2–2 at home against Mora in February. Before that, in January, Leksand actually won very surprisingly 4–3 over Mora in the district’s cup final postponed from last year. Of course, it gave courage and hope to the Leksand players.

How were the matches and the way of playing then? Karl Johansson, the only one in the Leksand team who played already in the first ice hockey match against Mora in 1938, much later remembered the Canadian fights:

”It was tough hockey. My defenceman friend Edvin Andersson was standing down by our zone when a Canadian came at full speed and hit him over. Edvin went straight into the boards. I had to take Edvin under my arm and go to the bench. But I didn’t get him in through the door, he didn’t want to. He shook his head and said, ‘I see him, I see him’ ... And they both fell, but the Canadian patted Edvin on the shoulder and laughed, ‘Okay, okay’. But it was not fighting, just hard play.”

Of course, the Canadians’ more physical style of play was something new both to the Swedish players and the audience. “Puck fights that won’t be forgotten,” a journalist wrote.

Leksand had, among others, 19-year-old Åke Lassas in its team, this season he was a dangerous forward but later in his career he would play defence. He received the first Guldpucken (The Golden Puck) in 1956 awarded to Sweden’s best player. Åke is still the player who has played most seasons in Leksand’s IF: 23 seasons (1940–1963) which probably is unbeatable. His jersey is of course retired in the rafters in Leksand.

In addition to Mora and Leksand, the Canadians also played away games outside the county border, against teams from Bollnäs, Hofors and Sandviken. The 2–1 victory away against Sandviken, a team which undefeated won Division II North, was the season’s main merit.

The majority of these Canadian servicemen were repatriated to England in the spring of 1944 while some remained in Sweden over the summer. One of them even married a Swedish girl. But four of these Canadian ice hockey players also died during new bombings later in the war.

Did not the Americans play ice hockey? Well, a co-pilot in a B-17 Flying Fortress named John Dutka (from New Hampshire) was the goaltender of Falu BS in the last match of the season against Leksand, states a newspaper article.

What happened next?

When the Canadian Halifax bomber pilot Harry Read in the summer of 1944 returned to his hometown Medicine Hat in southern Alberta, he was interviewed by the local newspaper about his more than six months as an internee in Falun. He said about the hockey season:

“We Allied internees had our own team and were permitted in some cases to travel to neighbouring villages to play opposition games. We nearly always drew huge crowds, but I think it was more the novelty of seeing the fliers, than the hockey display that formed the attraction.”

But for Leksand’s IF the matches had been important. Until 1943 Leksand’s IF had played only 18 matches in total since its first match in 1938. However, in the winter of 1943/44 they played 13, eight of which were against the Canadians. Leksand won five of the eight against these North Americans and the sport of ice hockey had now gained a foothold in Leksand.

The club’s ice hockey section’s chairman Karl Johansson, however, wrote quite cautiously in the section’s annual report: “The season has been one of the liveliest since ice hockey was started in Leksand.” The victory against Mora in the district’s unofficial cup final he emphasized as Leksand’s best merit.

Although there were only three teams; Falun/Canada, Mora, and Leksand that formed the historic first hockey league in Dalarna this winter, everybody agreed that hockey had had its breakthrough in the county this winter.

But hockey was nothing that everyone was familiar with in Leksand of 1944. A woman went to a store to buy a present for her young nephew. She said:

“I don’t know if it’s wet or dry, but it’s called a puck!”

The 1943/44 season, and those following, would soon contribute to changing the way of life in Leksand forever, leading to the growth of hockey for the entire nation.

The next winter, 1944/45, the last winter of war, there were no Canadian hockey players to light up the dark Swedish nights, but the sport would soon develop fast. Leksand played in the third division, while Mora finally was allowed to play in the second division. And immediately in 1945 Mora manage to qualify for the first division, the highest league in Sweden.

The fact that Mora played at the highest level of Swedish ice hockey actually benefited the hockey of Leksand too. Because when Mora’s opponents passed Leksand on their way to or from a match in Mora, Leksand was not late in offering the top teams training matches. During the 1945/46 season, Leksand therefore met all the teams in Division I North except Södertälje.

“That was our salvation,” Karl Johansson remembered more than five decades later. “It was in these matches that we got to learn to play ice hockey, in that we got to play against teams that were much better than us. There we learned team play.”

Only two years later, Leksand’s IF was also promoted to Division I, and in December 1948, the two teams Leksand and Mora met for the first time in the highest league in front of 2,500 spectators in Mora. Three weeks later over 3,000 came to the rematch in Leksand. In 1948, the two clubs also got their first national team members: Sven Kristoffersson (Mora) and Åke Lassas (Leksand).

Following the rapid new successes, the memories of the “Canada season” 1943/44 would soon fade, to be almost completely forgotten today. This was probably largely due to the fact that the airmen remained anonymous in the press, because of the censorship during the war. And the airmen who survived the war certainly remained completely unaware of their basic contribution to the future popularity of ice hockey in Dalarna. Instead other, more well-known Canadian, American and British-Canadian teams would continue the tradition to play in Mora and Leksand in the 1950s.

Ten years later, in 1954, there were no less than twelve (!) ice hockey rinks with electric lighting in the Leksand municipality, including the 1954 inaugurated new outdoor ice stadium with room for 8,000 spectators (in a municipality with about 9,000 inhabitants in the 1950s). Interest had completely exploded. Leksand’s Ice Stadium was then artificially frozen in 1956 and roofed in 1965. The ice rink in today’s Tegera Arena is actually located in exactly the same place as the rink was in 1954, and only 200 meters from the place (now a parking lot) where Leksand played the Canadian airmen in 1944.

The significance of the matches

Leksand played its first Swedish Championship play-off in 1956. In the same year, the chairman of the Dalarna Ice Hockey Association, Thore Mattsson, looked back in the association’s ten-year publication. There, he highlighted the importance of the Canadian airmen for the hockey in the district: “For some years it seemed hopeless to get more clubs start playing hockey, partly because of the war, partly because there was some suspicion of this new sport in Dalarna. During 1943/44, Canadian airmen were interned in Falun, and some of them were interested in playing with the hockey team in Falun. They were not the biggest stars on the hockey scene, but the press wrote a lot about them and this PR was probably the best conceivable for the sport of hockey. After their guest performances, we got wind in our sails, and year by year the number of clubs in Dalarna increased and now we are a relatively large hockey district, the largest in Sweden after Stockholm.”

In 1956, Leksand’s IF team leader Arne Hellberg also remembered for the magazine Rekord’s reporter the matches against the Canadians in the winter of 1944:

“Of course, we arranged quickly so we got to both train with them and play with them, and in this way our game culture was founded, which I think we can now be proud of. But they were the tough guys, the Canadians. There were hits all over the place. I myself played as a center against the Canadian airmen. They were really intense players, you see, and at least you had to learn to withstand hits.”

So now nearly 80 years later, how will the importance of the Canadian airmen for the hockey of Dalarna and Leksand be assessed? It is of course difficult to value. After all, it is just a short winter of playing, for a few months. But one can see it the other way; what would have happened if these matches had not been played? What would have happened if ice hockey in the county had not been revived in 1944?

Leksand’s IF might have missed out on league games for another season, interest might not have been so well-founded, the players might have moved, they might have invested more in soccer or other sports: For example, Anders Brisell was already playing in the top league in soccer with nearby IK Brage. Åke Lassas was another good soccer player who in 1948 – as a soccer player – was offered to move to AIK of Stockholm. But he declined and stayed at home in Leksand. In addition, Sigge Bröms was a young talented slalom skier who was given an ultimatum by the hockey team: choose between slalom and ice hockey! He chose ice hockey and became Leksand’s first ice hockey world champion in 1953.

Since then, many Leksand players have played for the national team in the Olympics and the World Championships. In the 1976 inaugural Canada Cup six of the Swedish players came from Leksand.

The Canadian legacy

Leksand’s IF won the national championship in 1969, 1973, 1974, and 1975. Today Leksand plays in the Swedish Hockey League, the SHL. In 2022/23 Leksand is playing its 61st season in the highest league, and it is the ice hockey club with most fans in Sweden. In 2021/22 Leksand also played in the European Champions Hockey League, CHL.

There’s a Canadian legacy in Leksand. The club had had both Canadian coaches and players, recently including the 2021/22 SHL MVP Max Véronneau. But the Leksand players have of course also moved to the NHL. Through the years 103 (and counting…) NHL players, both Swedish and foreign, have played for Leksand! Seven of them have won the Stanley Cup: Tomas Jonsson, Ulf Samuelsson, Kjell Samuelsson, Ed Belfour, Jiri Bicek, Ric Jackman, and Michael Ryder.

Leksand native Lars-Erik Sjöberg (1944–1987) was the first European player to captain a team in the NHL, for the Winnipeg Jets in their first NHL season 1979/80. Lars-Erik Sjöberg who played defenceman behind “The Hot Line” - the legendary trio of Bobby Hull, Anders Hedberg and Ulf Nilsson - won three Avco Cups with the Jets. He was posthumously inducted into the team’s hall of fame in 2019. Thomas Steen, who played in Leksand’s IF from the age of 16 to 20, also joined the Jets in the early 80s. His jersey number was retired by the Jets in 1995, the first European player in the NHL to receive this honour. Today Filip Forsberg of the Nashville Predators is the biggest NHL star who grew up in Leksand.

In January 2022 Patrik Allvin from Leksand became the first Swedish general manager in NHL history when he was officially announced to the position by the Vancouver Canucks. In April 2022 Leksand native Emil Heineman signed a contract with the San Jose Sharks, and in June 2022 Leksand native Isak Rosén signed a contract with the Buffalo Sabres. In May 2022 Canadian Jordan Colliton was appointed as the head coach of the women's hockey team in Leksand (also playing in the Swedish highest league, the SDHL).

A small town with a big team, Leksand has been described as more Canadian than Canada itself. Wayne Fleming coached Leksand for four seasons in the 1990s. He concluded: “It’s an ice hockey environment. You live and breathe ice hockey 24 hours a day!” In 2007 Canada won the Junior World’s final against Russia in the brand new arena in Leksand.

Since 1976, thanks to hockey, Leksand also has a twin city exchange with Aurora, Ontario. The Olympic city of Lillehammer in Norway is another twin city ever since World War II.

The Leksand defender Åke Danielsson, who won two national titles with Leksand in the 1970s, has in recent years diligently devoted himself to inventorying all the ice hockey rinks that have ever existed in Leksand’s current municipality (which according to the municipality’s own marketing “consists of 94 villages”). To date, Åke has mapped over 60 different outdoor hockey rinks of various sizes! Clearly, there is a sports heritage in these that also explains the uniquely strong interest in ice hockey in Leksand.

Rune Joon, the former CEO of one the biggest local companies, the bakery Leksand’s Crispbread, was right when he said at the end of the 20th century: “Ice hockey is for Leksand what the Eiffel Tower is for Paris.”

The story continues since one of the Halifax bombers was found again

6,176 Handley Page Halifaxes were built during the war, but after 1945 all those remaining went to the scrapyards. Not a single aircraft was saved. Nonetheless, today there are two completely restored Halifaxes displayed at museums thanks to extensive recovery efforts (one in England and one in Trenton, Ontario).

Then all of a sudden, in 2011, the Swedish Coast Guard found a Halifax bomber off the Swedish coast. It was one of the aircraft in this story, HR871, which was hit by lightning during the Battle of Hamburg in August 1943! Now the wreck is salvaged by the organization Halifax 57 Rescue Canada, part by part from the brackish water of the Baltic Sea, hoping to rebuild the plane at the Bomber Command Museum in Nanton, Alberta. The next efforts will be made by Swedish divers in the summer of 2022. The amazing project, led by Karl Kjarsgaard of the Bomber Command Museum, has gained national attention both in Canada and in Sweden.

But until now, nobody knew that among this crew there were Canadian hockey players who unexpectedly played a full hockey season in Sweden in 1943/44. Who were they, who were the other crews and what really happened? Read the full story about their incredible journey and their time in Sweden in the book “The Canadian airmen and Leksand’s IF” (published only in Swedish so far).

Copyright 2022 Lars Ingels.

-------------------

About the author:

LARS INGELS, born in 1968, M.Sc. (Econ.), previously worked at Leksand’s IF Ice Hockey’s marketing department. Today he is active as a freelance writer. He has written more than ten books, mainly in the field of sports history, both on the Winter Olympic Games and on Swedish ice hockey.

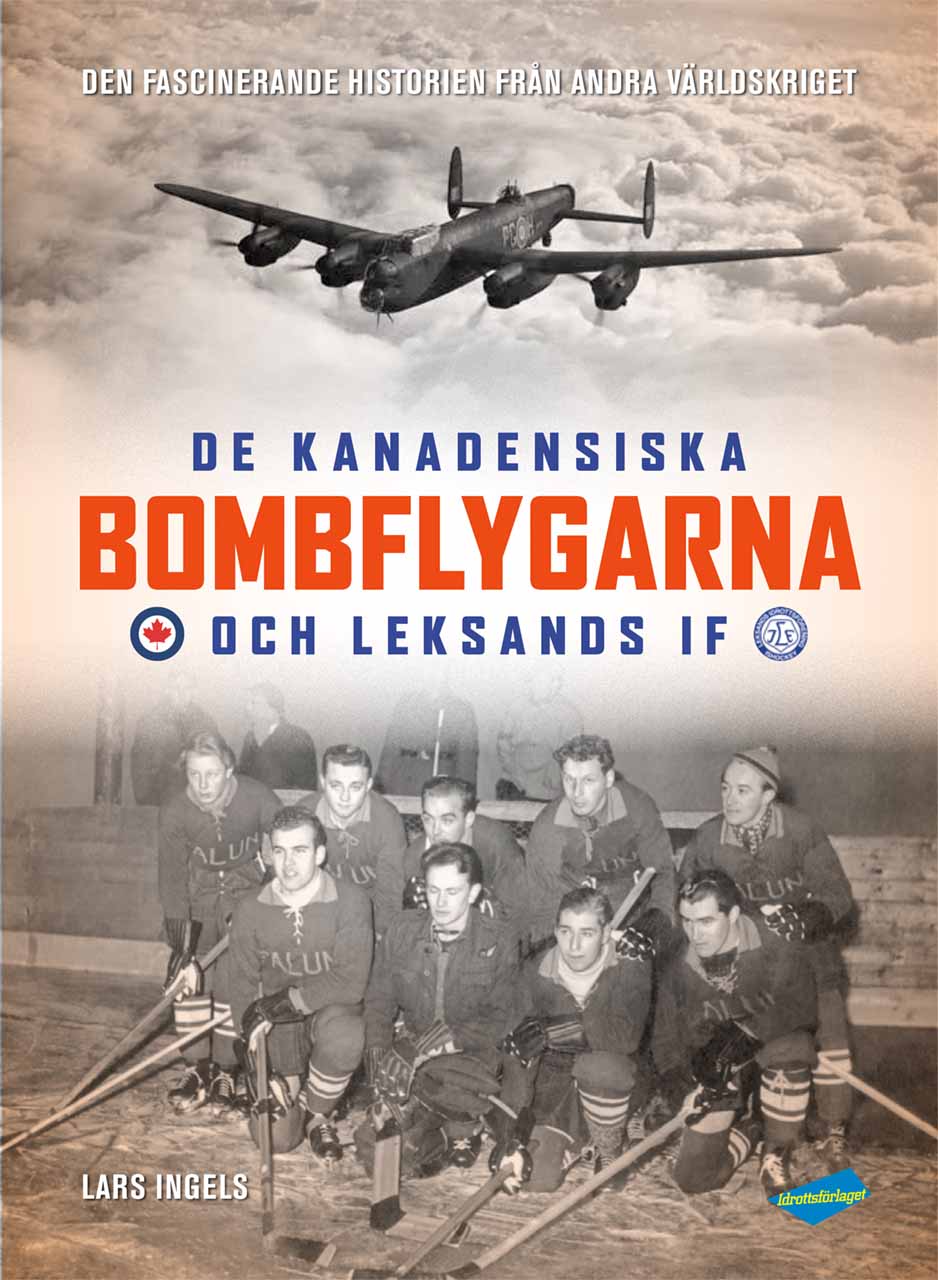

The book “The Canadian airmen and Leksand’s IF” was published in Swedish in 2019.

DOWNLOAD HIGH RESOLUTION BOOK COVER:

Download here (jpg 1.6 MB)

Lars Ingels’ book “The Canadian airmen and Leksand’s IF” (De kanadensiska bombflygarna och Leksands IF, published by Idrottsförlaget in 2019). It is a true story of an unlikely season, which would contribute to change life forever in Leksand, the small community in Dalarna county, Sweden.

PHOTOS:

CAPTION: The rear part of a Halifax bomber, DK267, on a courtyard in Annelöv in Skåne where it crashed in August 1943. Photo from the book ”De kanadensiska bombflygarna och Leksands IF” and Swedish Forced Landings Collection.

CAPTION: Photo of the crew from the Halifax bomber HR871 at Främby internment camp in Falun. Back row from left: Alwyn Phillips, Vernon Knight, Herbert McLean, Wilfred "Joe" King, the Swedish lieutenant Torkel Tistrand. Front row from left: A Swedish unknown military, Ronald Andrews, Bill Mainprize, Lloyd Kohnke. Photo from the book ”De kanadensiska bombflygarna och Leksands IF”.

CAPTION: Autumn in 1943. Crew from HR871 at the cobbled Main Square in Falun (Slaggatan, Stora Torget) . From left: Herbert McLean, Vernon Knight, Bill Mainprize, Joe King.

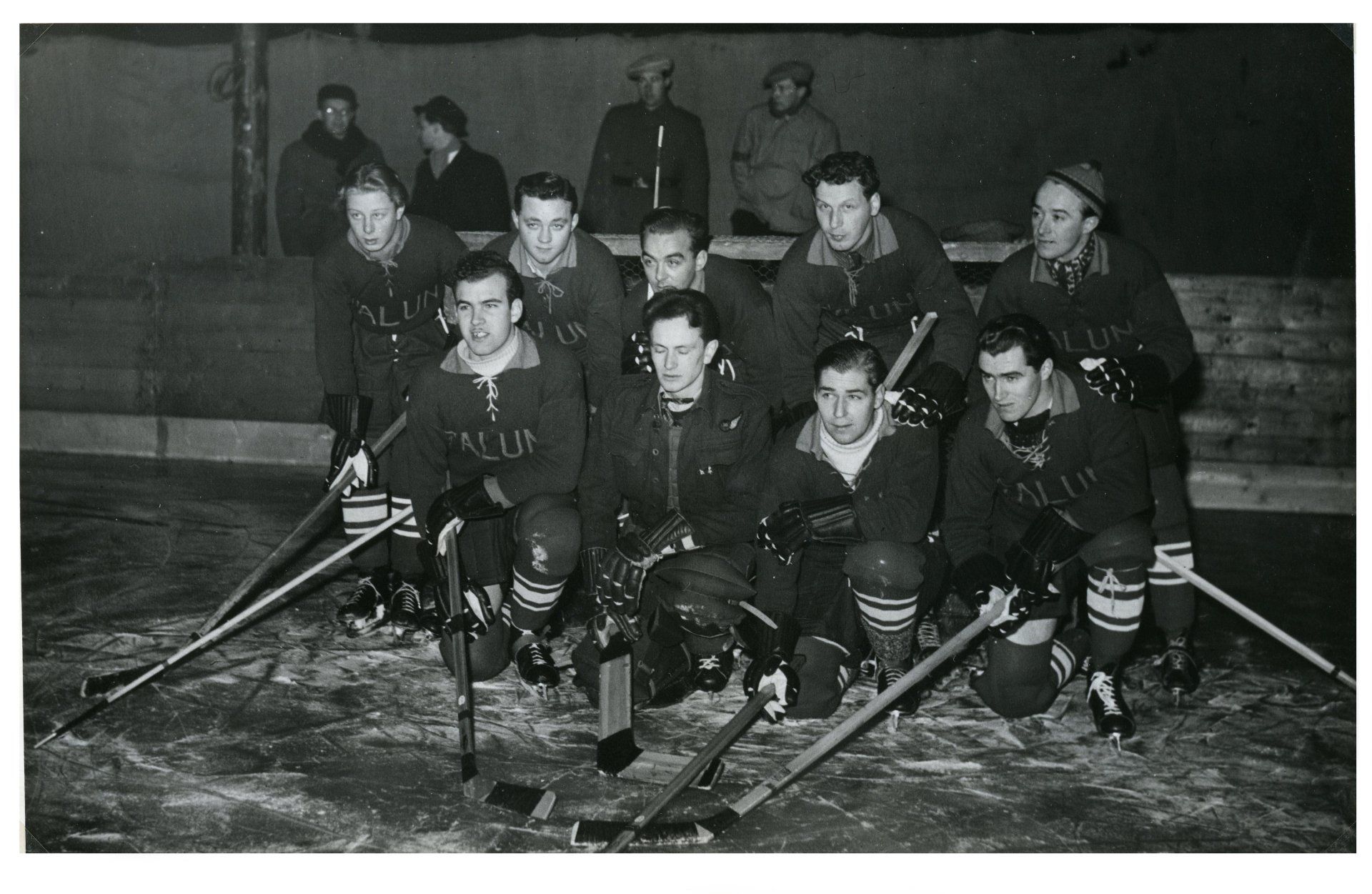

CAPTION: The combined Falun-Canada team that played the first match in Falun against Mora. Back row from left: Stig Nordström, Bill Mainprize, Robert Ginson, Ragnar Mattsson, Olle Holmén. Front row from left: Jim Flick, John Gates, Joe King, Lorne Cassidy. Photo from the book ”De kanadensiska bombflygarna och Leksands IF”.

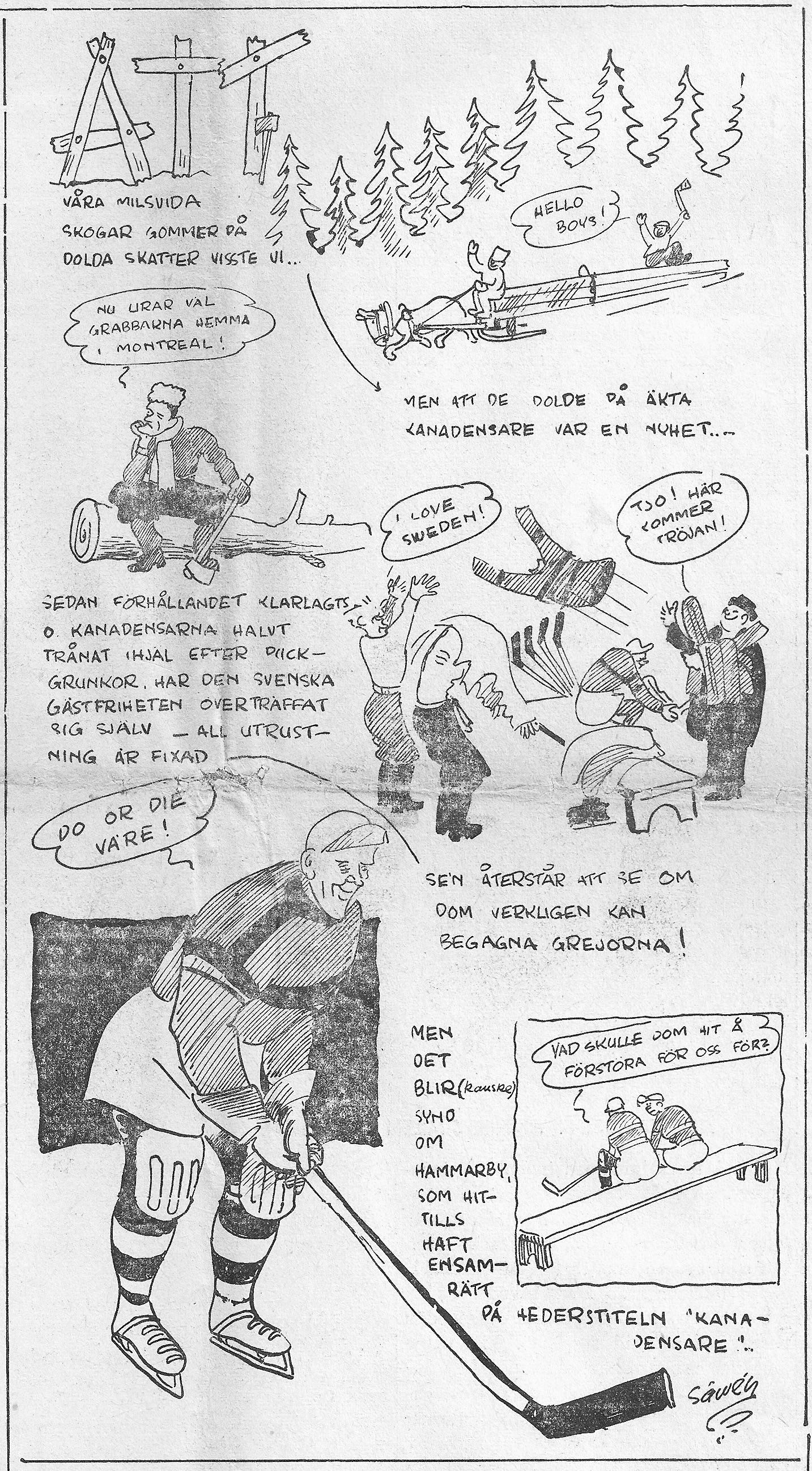

CAPTION: Cartoon from the magazine Idrottsbladet before the Canadians’ first hockey appearance in Dalarna. From the book ”De kanadensiska bombflygarna och Leksands IF”.

CAPTION: From the Canadians’ first match in Mora on New Year’s Day 1944. The Mora players have light pants and hats. Photo from the book ”De kanadensiska bombflygarna och Leksands IF”.

CAPTION: This seems to be the only photo when the Leksand team and the Canadians were photographed together. Standing from left: Harald Andersson (Falun), Edvin Andersson (Leksand), Jim Flick (Falun), Åke Lassas (Leksand), Rune Bohlin (Falun), Anders Brisell (Leksand), Walter Kroeker (Falun), Nils Holfve (Leksand), James McQuade (Falun), Olle Årjers (Leksand), Ragnar Mattsson (Falun), Arne Hellberg (Leksand), Bertil Hansson (Falun). Kneeling from left: Ingemar Söderberg (Leksand), Einar Jonsson (Leksand), John Gates (Falun). Photo from the book ”De kanadensiska bombflygarna och Leksands IF”.

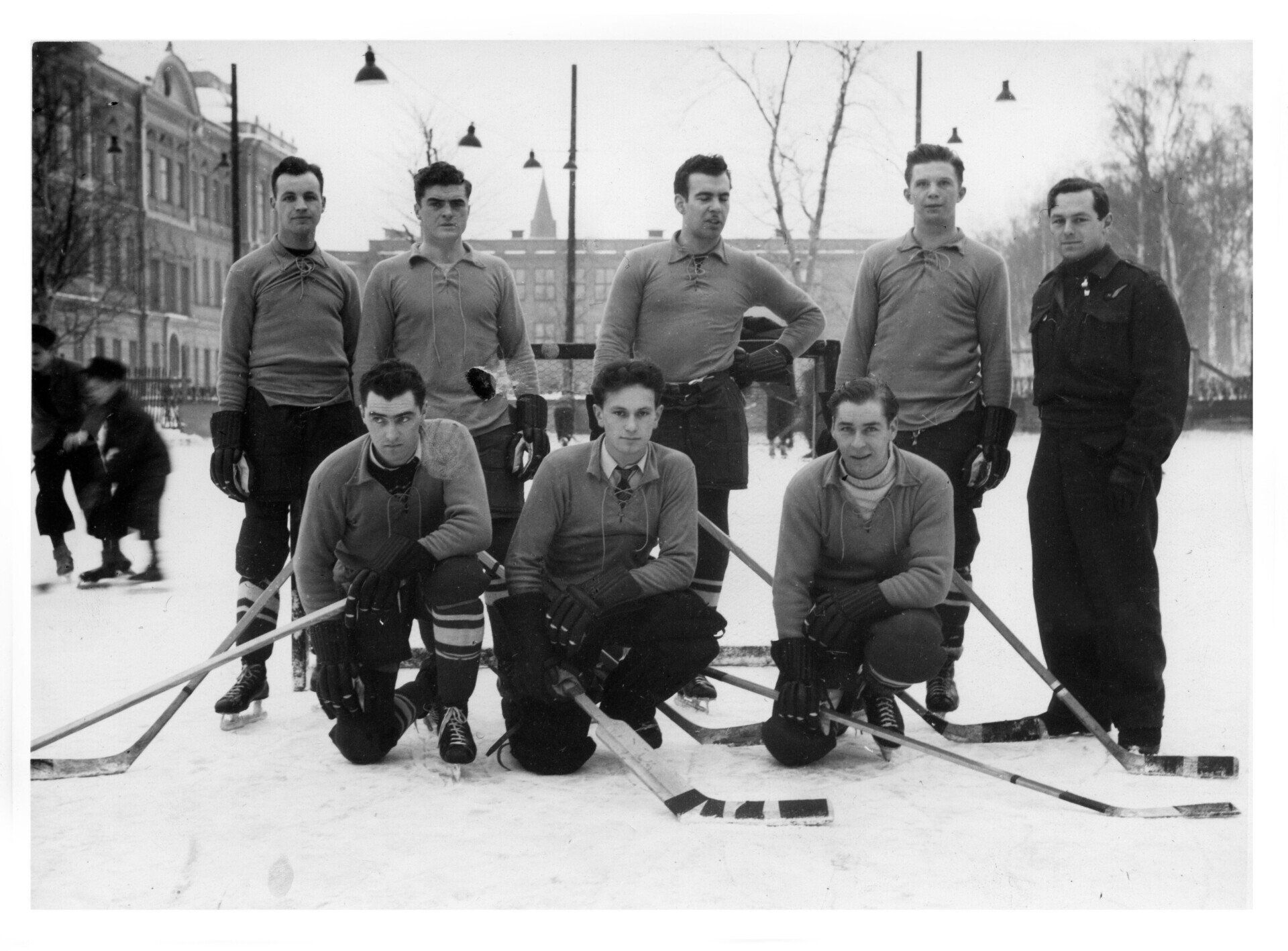

CAPTION: Training at the new rink in Falun. Only four of these eight Canadians survived the war. Back row from left: William Smith, James McQuade, Jim Flick, Walter Kroeker, Peter Davies. Front row from left: Lorne Cassidy, John Gates, Joe King. This photo was taken some time between January 10 and January 30 in 1944. Photo from the book ”De kanadensiska bombflygarna och Leksands IF.”

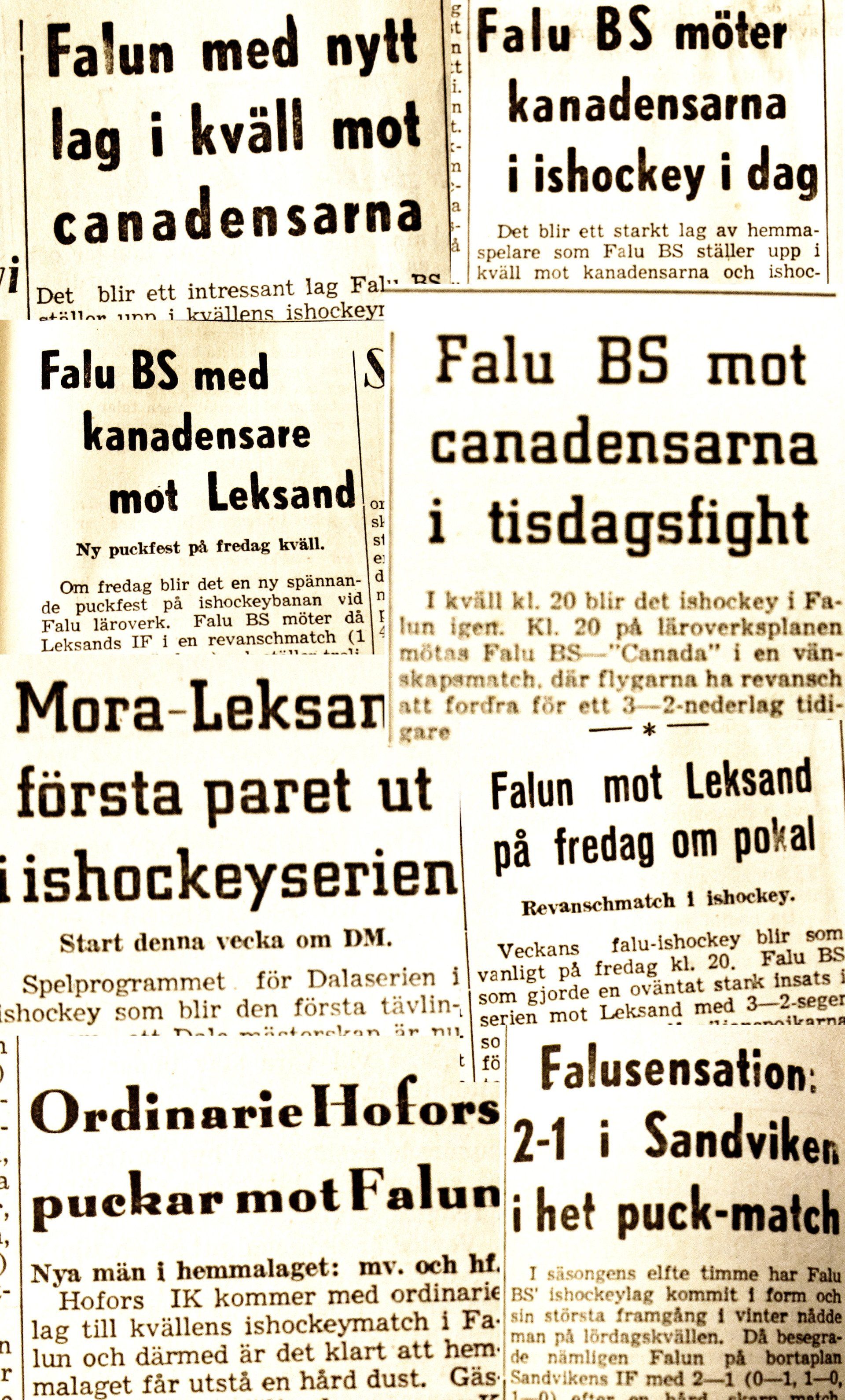

CAPTION: Collage of newspaper headlines from the Dalarna press in 1944. From the book ”De kanadensiska bombflygarna och Leksands IF”.

WATCH THE BOOK TRAILER: